#12: Chest Cancer

COMMUNITY VOICE: Eli Oberman | HEALTHCARE EXPERTS: Madeline Deutsch, MD, MPH; Alexes Hazen, MD | COMMUNITY REVIEWER: Preston Allen

SHOW NOTES

Defining our terms

Chest cancer, you say?

What we’re referring to: a diagnosis of cancer in the soft glandular – or breast - tissue overlying the pec muscles

Anatomical labels come with gendered baggage, but – as our community voice, Eli, highlights - the experience of breast/cancer as a transmasc person is a highly gendered medical/cultural phenomenon. We preferentially use chest cancer, but will echo the language our experts use throughout the episodes

Who’s this episode for?

Focuses on chest cancer in non-binary and/or transmasculine folks who were assigned female at birth and have gone through puberty such that they developed chest tissue

This includes folks who:

Have and have not had top surgery

Have been on T, are currently on T, or have not been on T

Testosterone? Cancer? Say more.

The big take away point: we don’t know enough to make clear cut, data-based decisions.

In biological theory-land:

Testosterone is a precursor molecule for estrogen. Some chest cancers grow more when exposed to estrogen. So there is a theoretical concern about gender affirming hormone use – testosterone – potentially increasing someone’s risk of breast cancer.

Repeat: it’s unclear if testosterone use affects chest cancer risk.

What does this mean in practice?

There isn’t one right answer about how to medically manage gender affirming hormones after a diagnosis of chest cancer.

Whatever the right answer is will be the result of an informed conversation with a health care consumer about their priorities, which should include the theoretical risk of worsening cancer vs. the evidence-proven, life-saving effects of gender affirmation through T.

A redux of surgical options

FYI - we will using the word breast here for anatomic specificity.

Refining our surgical vocabular

Lumpectomy: the removal a view centimeters of breast tissue; this can be one way, depending on size, of removing cancerous tissue

Mastectomy:

Means the removal of breast tissue, plain and simple.

Most often discussed in the context of cancer treatment - in which case, the goal is to have all breast tissue removed, as anything left over will leave a residual risk of cancer

But as an FYI, some people refer to top surgery - more on this below - as a gender-affirming mastectomy. The big point is that it’s not the term itself, but the goal of the surgery, that guides what actually happens in the operating room.

Top surgery:

Most often refers to a gender-affirming surgery to remove chest tissue.

Leaves breast tissue to help contour or shape the chest.

Depending on the specific surgical technique this may leave nipple sensation and the nipple itself intact.

Why does this all matter?

It is technologically challenging to screen people for chest cancer after they’ve had top-surgery - more on this below.

The upshot: someone with a risk of chest cancer may not know their ability to check for cancer via the usual standard of care (a mammogram) is limited

Our belief, echoed by several of our expert voices: someone who has a high risk of chest cancer and who is pursuing a gender affirming mastectomy should have a detailed discussion about their personal cancer risk

What do we know about the baseline risk of chest cancer in transmasculine folks?

Two studies that have looked into this:

A Dutch study concluded rates of breast cancer in transmasculine folks are overall low.

A Veteran’s Administration study found the risk is somewhere between cisgender male and cisgender female populations

Why these studies don’t really move us

Neither of these looked at the amount of chest tissue, prior surgeries, or hormone use

So it’s difficult to know how to counsel people re: their cancer risk based on the results

#NotEnoughData, but screening should be a joint decision

Screening for chest cancer

If natal chest tissue without top surgery:

A mammogram every year or two years

Same standard of care as for cisgender folks, basically

Screening for chest cancer after a chest surgery:

TL;DR: there are no established best practices or clear data for how to screen someone’s remaining chest tissue for cancer after a gender affirming mastectomy

Surely there’s something to pursue?

The usual modality, mammogram, doesn’t work as there isn’t enough chest tissue to place between the two parts of the machine

The alternative, MRIs, are costly, often not approved by insurance, and often have false positives - where we don’t have great data to guide us on what to do

Expert opinion: less chest tissue likely means less chest cancer risk, but that is not a researched question (yet!)

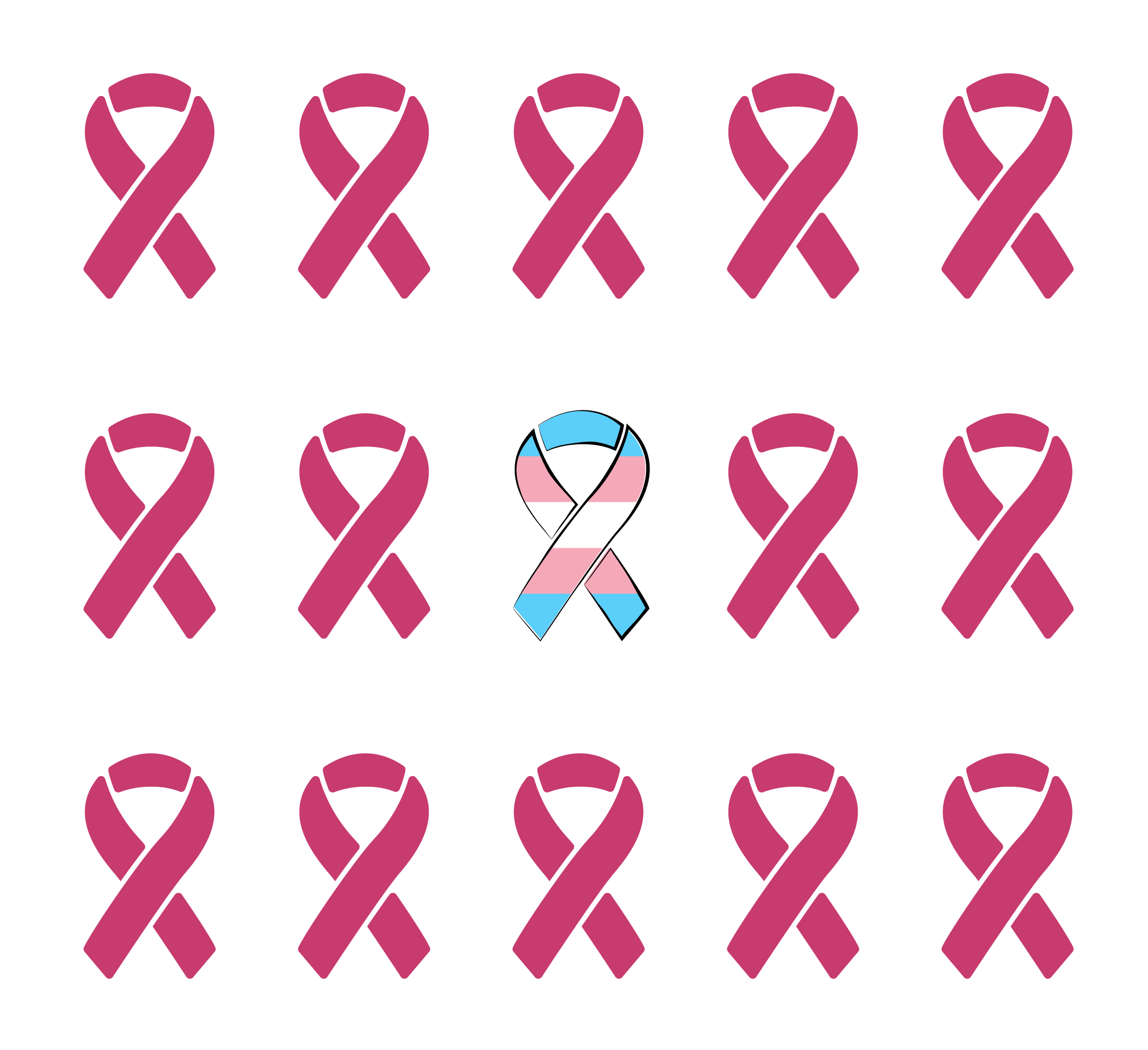

The “pink ribbon” dynamic

The medical system is big on gender. The medical system delivering breast cancer care is also big on gender - aggressively so, as Eli points out.

That makes going through this system as trans…fraught - and that’s an understatement.

Being in these gendered spaces exposes someone to a lot of potential (and usually experienced) stigma

That could include assumptions about losing chest tissue, changes to someone’s hair with chemotherapy, and even who is the patient when someone has a visitor with them.

Extra credit!

Does chest binding and testosterone impact chest cancer risk? Some data here.

Guidelines, guidelines, guidelines! (from UCSF, here)

What about other cancers? Some summarizing of current data here.

A nice overview written by one of our health professional experts, Dr.Deutsch!

TRANSCRIPT

Eli: the difference between, what people commonly call top surgery and what a mastectomy is in for cancer purposes are actually two different things. And that was not something I was aware of before. and that has become really important to me

[QHP THEME MUSIC STARTS]

Gaby: Welcome to Queer Health Podcast. QHP is a podcast about queer health topics for sexual and gender minorities.

Sam: My name is Sam. I use he/him pronouns, and I'm a resident – or physician in training to be a primary care doctor.

Gaby: I'm Gaby. She/her pronouns and same job title.

Richard: And I'm Richard. I use he and him pronouns, and I'm the director of LGBTQ clinical services at Bellevue Hospital in New York City.

Gaby: You're listening to QHP, season two, episode two: chest cancer for Trans-Masculine Folks.

[QHP THEME MUSIC ENDS]

Sam: At the start of the episode, we heard from Eli Oberman summarizing their experiencing navigating today's topic.

Gaby: And that topic is non-binary and transmasc folks who are dealing with a breast or chest cancer diagnosis and then treatment. This is where I wanna pause for a second because I wanna bring in the first disclaimer of this episode, which is that we're gonna use the word chest cancer in an attempt to take away a lot of the gendered baggage of what the phrase breast cancer might, but doesn't always evoke for some trans folks. I say words that we've spoken before on this podcast.: queer health isn't a monolith.So the topic of chest cancer doesn't impact all members of our community in the same way. We know, for example, that cis lesbians are impacted by chest cancer and they have worse outcomes when we compare them to their straight cisgender peers. But that's not the focus of today's episode. Instead, we're choosing to focus on non-binary and transmasculine folks with chest cancer. So this is just one thread within a large or queer tapestry.

Richard: This is a topic where we hope to add a little levity, but hope not to take away from the seriousness of this. We hope that you'll talk to your friends and healthcare providers about what and when to get screened for cancer, if that applies for you

Gaby: Of course, we hope that this episode is gonna get you up to speed on screening for chest cancer if you are planning or considering having your chest tissue removed.

Richard: And lastly, we'll get nerdy about what information chest cancer screening can actually give you if you've gone through top surgery. And spoiler alert: there's not a ton of scientific data

Sam: So buckle up for some excellent expert advice, but don't hold your breath for any clear cut guidelines,

Gaby: And with that uplifting thought, let's take that five second dance break that you've all been waiting on.

[TRANSITION MUSIC]

Eli: My name is Eli Oberman. I use they and he pronouns. I am a non-binary trans person and a musician and composer and a breast cancer survivor.

Gaby: Alright, let's talk diction for a second here.

Sam: Diction? ...Oh, nevermind. Different word. Sorry,

Gaby: I am ignoring you. I meant diction – like word choice. Like, Eli using the term breast cancer to describe his experience.

Eli: It's not because I think that it’s better. But my experience was so much about being and feeling unwelcome and, marginalized within all of the breast cancer world stuff as a non-binary trans person. Like, going into these extremely gendered and extremely feminized environments all the time. I really did feel like I had breast cancer, you know? So that actually feels the most accurate from my experience.

Richard: Today, we’ll mostly stick to chest cancer as this is less rooted in specific gender identity. But you'll hear us use both chest and breast throughout as – just like our experts – we try to echo the healthcare consumer or patient's preferred language

Gaby: Whatever term you wanna use, let's just get on the same page about what anatomy we're actually talking about here.

Richard: We're talking about cancer that comes from a part of the body or tissue that sits on top of the chest wall muscles, or what we call the pectoralis major. And though some may use the term “chest tissue," we wanna be clear that we're not referring to this in context of muscle or other parts of the chest – like ribs, or any of the soft tissues.

Sam: Okay, and with that, let's get back to Eli in the beginning of their chest cancer story.

Eli: I was 27. When I was diagnosed, I had no family history and they really couldn't figure out, you know, a reason why I had it. And so the very first thing that they thought was maybe this is because of testosterone. I had been on testosterone for about seven or eight years at the time. and well, the, like, recurring theme here is "We have no idea what to do with you.” And so they were like, "We have no idea what caused this, but maybe it's T there's no literature on that. We have no idea. So why don't just to be careful, why don't you just stop?" So they had me stop hormones, just cold turkey. Which, ou know, not a good way to do that for anybody. And so on top of feeling, you know, emotionally distressed about having a cancer diagnosis I also just was a hormonal basket case.

Gaby: A new cancer diagnosis, hormone withdrawal. It's already not a great situation, but there's another layer of this, which makes it even worse, which is the ambiguity of it all…the ambiguity around what actually caused Eli's cancer in the first place.

Sam: We know that with most cancers, there's often multiple things contributing to what makes them grow. Usually, this is some combination of the person's underlying genetics and combined with the things they've been exposed to in their environment.

Gaby: And in Eli's case, exposures included the testosterone he'd started taking as part of gender affirmation. But even though in his story testosterone did get saddled with the blame, I'm still kind of wondering: did testosterone actually cause Eli's cancer? Or anybody's cancer for that matter?

Richard: Bring in the expert.

Deutsch: Hello. I'm Maddie Deutsch and I am a physician. I'm the medical director for the Gender Affirming Health Program at the University of California, San Francisco, where I am an Associate Professor of Family Community Medicine. And I'm also the president-elect of the US Professional Association for Transgender Health – though my appearance here today is as an individual and not representing that organization.

Richard: Dr. Deutsch gave us the biological explanation for why testosterone is in the cancer causing hot seat.

Deutsch: There are some mechanisms. You know, testosterone – and it gets aromatized to estrogen. Does that result in more estrogen?

Sam: “Aromatize” is a fancy way to describe how an enzyme takes testosterone molecule, changes it a little bit and converts it to estrogen. So in a perfect little science theory world, maybe testosterone could be more estrogen.

Gaby: However…

Deutsch: A lot of theoreticals, but there hasn't been a great deal of data to support that there's any kind of significant increased risk.

Gaby: This is all hypothetical, and the variation across bodies and hormone backgrounds really complicates the theory.

Richard: Not to mention the variation across cancers. There are many different types of chest cancers. Some of them are revved up by estrogen and some of them aren't.

Gaby: And so this is obviously a difficult, confusing dataless dance we're doing. And the question is: how do you continue gender affirmation with hormones while also ensuring that you aren't making a new cancer diagnosis worse by giving the cancer fuel to grow? And I think in the best case scenario, a doctor's actually going to hold that ambiguity with a patient and have an honest conversation where they say, “we're in a gray zone” and “let's navigate that gray zone together." And "I will take you every step of the way.” But I think it's also really important to acknowledge that doctors really don't do well with gray zones. Right? It's one of the things we've mentioned time and time again on our podcast as an area for continued improve. And that's where this topic gets really, really tricky.

Richard: And to your point about areas for improvement, I think it's really important for us to recognize that there are many clinicians out there who don't feel comfortable prioritizing someone's value for their gender affirming hormones while also treating their cancer.

Sam: Right? There's probably so many clinicians who aren't gonna give the patient the time, the space, the agency to express what risks and unknowns they're okay to live with in the context of continuing gender affirming care with a cancer diagnosis

Richard: That's a real problem. You may need to find another doctor or at least have a deeper conversation with the one that you have, even if that's ultimately the answer you arrive at. You need to be seeing someone who will both share what your views and needs are for your gender affirmation, and also try to do their best to help you with cancer. There may not be one right answer.

Gaby: Yeah. I mean, I think it's becoming abundantly clear that there definitely isn't a right answer.

Eli: I was really lucky in the process to have really amazing chosen family to help advocate for me, which is something I'm extremely grateful for. The friend who really helped advocate for me with my oncologist and, you know and say, “Okay, We don't know. So can we have me, like, go back on hormones until we have any real information that this is related.” And they agreed. So I went back on. We did end up, you know, changing my testosterone throughout the process to try to deal with some of that. bBt in a much better, more thought out way than at the beginning.

Sam: Eli's next step in the process was to discuss how to get rid of the cancerous tissue through surgery.

Eli: Everyone kept saying to me: “This is so horrible. I'm so sorry. This happened to you, but silver lining, you get free top surgery.” And I was like, “Okay, actually, that's making a lot of assumptions about my gender and I didn't want that.”

Richard: You've heard us say in season one, and now you can hear us say it again in season two: surgery’s not for all trans people and does not define transness.

Eli: When I started identifying as trans, I wanted top surgery. And like a lot of other people, it was just so financially out of reach that I never even, like, had a consult and, and chose to do hormones instead, because it was so much more available and affordable. And by the time that I was diagnosed, I had actually, come to a really different place about my gender and my body. And I had actually decided that I didn't want top surgery anymore. And who knows if I would've changed my mind again later? But at the time I was actually feeling like I could look in the mirror and see who I was and felt like I was comfortable in my body and I felt like other people were responding to me appropriately with my gender. And so, you know, there was – there was definitely a lot of irony around that. I felt a lot of guilt about it actually. I felt like I was getting something that that I didn't want, that I knew so many other people wanted and couldn't afford.

Gaby: One small clarifying point: just because Eli's cancer required a removal through surgery, doesn't mean everyone's does.

Sam: Many folks undergo a lumpectomy or the removal of a specific area of the chest or breast tissue rather than the whole chest or breast tissue. But the details of Eli's specific diagnosis warranted a mastectomy or removal of all the breast tissue.

Gaby: “Mastectomy" and “top surgery,” I find, are often used interchangeably because they're referring to surgical removal of breast or chest tissue. I will say I do feel like I hear top surgery used specifically for gender affirming procedures. A mastectomy is kind of a larger umbrella term that can apply to gender affirmation or to other reasons to have your chest tissue removed, like cancer. Anyway, this is vocabulary mumbo jumbo, but the bottom line is that whatever words you're using, it's important to know there actually are different procedures depending on what your goals are.

Eli: The point of top surgery is to create a quote unquote male appearing chest. And it's an it's aesthetically driven and it's not cancer related. If someone has had, you know, traditional top surgery and their chest appears to be quite flat, there's actually a significant amount of breast tissue still left in.

Gaby: When the surgery is also geared towards treating or preventing cancer, you're actually going to remove all of the breast or chest tissue that might be cancerous.

Eli: That has become really important to me because it's not something anyone I've talked to has been aware of either. And I believe that we should all be able to make informed choices about our healthcare, regardless of what you decide. And that is seeing the lack of understanding about that has been really worrisome to me

Gaby: This seems like a perfect time to bring a surgeon and to talk more about this.

Hazen: My name is Alexis Hazen and I'm an Associate Professor at the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic Surgery at NYU Langone Health. I am also in private practice, which focuses on transgender health care, anti-aging and wellness.

Gaby: When Dr. Hazen started talking about the specifics of chest surgery, the first thing that she emphasized was that there's no one size fits all set of procedural options.

Hazen: So a gender firming mastectomy – you know, in a way, it's hard to talk about it generically because it depends a little bit on what technique you're using. And that depends on patient's desires and also their particular anatomy. And some people haven't really thought about it very much. And they haven't thought about sensation, and they haven't been thought that they're even options. And – and it's as if they thought there was only one possible surgery. So we talk about what, what their desires are and how they really want things to look and feel. And then based on that, we make a decision. Also, including their personal risk factors connected to breast cancer.

Richard: To be clear here, we're talking about people who have their natal chest tissue and have gone through a puberty to develop more breast tissue and not necessarily people who have a diagnosis of chest cancer.

Gaby: And this is different than Eli's story, where top surgery was really only on the table after they were diagnosed with cancer. But surgeons like Dr. Hazen think about theoretical risks of cancer for anyone they're operating on, even if they don't have an active cancer diagnosis.

Hazen: If somebody has a higher risk for breast cancer, then I'm only going to do one type of mastectomy, which is a mastectomy where I remove the breast tissue so that their risk then for developing breast cancer is as low as possible going towards the future. If somebody has a personal, very low risk breast cancer – family history is low – then I would consider – if they were a candidate – doing a different technique where I might leave a little bit of breast tissue. Let’s say they want to keep nipple sensation, that's very important to them. The only way you can do that is if you leave a little bit of breast tissue connected to the chest wall, but then that increases the potential, you know, ongoing risk of breast cancer because you haven't done a full mastectomy.

Gaby: Dr. Hazen’s approach is twofold. First, what do you want from your gender affirming mastectomy in terms of your aesthetic goals? And then two, do you have a high risk of chest cancer – and how does that factor into the conversation?

Sam: Just as an FYI: Eli pointed out that Dr. Hazen's cancer conscious approach is a rare one. Eli's big takeaway is that many people in the community aren't talking about these risk factors. And this nuanced conversation about the tissue that's left over after surgery and the cancer risk that's left over after surgery rarely comes up.

Eli: By giving all these people, top surgery and leaving a lot of breast tissue in, you're creating a population that:

A. Don't know that there aren't risk.

B. Are not any more physically capable of having a mammogram as a checkup

Sam: So we'll get into that more later. But for now, suffice to say mammograms are not really designed to function when there's not a lot of physical chest tissue there.

Eli: …and

C. are extremely averse to going in for any kind of medical thing around that part of their body and I've had negative experiences.

..So all of those three things, things combined really is creating a population that's at risk and doesn't know that they are risk. And that was really disturbing to me.

Gaby: A follow-up question that at least I am asking myself is: what do we know about the baseline risk of chest cancer in trans men? Like – is there data that would help people understand their risk of cancer and that might help them make a decision about what type of surgery they might opt for?

Sam: Dr. Deutsch spoke to two studies that address the baseline chest cancer risk in trans-masculine people. One is a study from Holland and the other is out of a Veteran's Administration in the US.

Deutsch: The study kind of found conflicting findings, right? The Dutch concluded in their own – their interpretation was that rates of breast cancer in transmasc people are low. And the VA study found somewhat, somewhere kind of in the middle between cis male and cis female risks.

Gaby: So the two studies pointing in opposite directions doesn't actually surprise me very much because there's a lot of variables that were left undefined. Neither study gets into how much chest tissue people had left, and we also don't hear anything about what their gender affirming hormone use looks like, whether they were auntie or not.

Deutsch: Now, the question comes in: are there specific factors for transmasc people who have or have not taken T that make their risk different and potentially increased compared to ciswomen? That answer does not exist.

Gaby: And this is a lot of unknown and that makes it really hard to make conclusions. It also makes it really hard to figure out how to apply this to anyone's specific medical journey.

Richard: Altogether now... [silence] All right. Basically, not enough data.

Gaby: I – I can't say it more than once, [laughter] Anyway…

[TRANSITION MUSIC]

Gaby: Okay, let's talk about chest cancer screening,

Deutsch: The reality is that if you have not had chest surgery and then your screening should be similar to a cis female.

Gaby: And by that she means a mammogram. More on this in a second.

Deutsch: Now those recommendations are fairly well developed and based on pretty solid evidence for cis women.

Sam: A mammography machine is designed to take chest tissue, smush it between two plates, and send x-ray beams through those plates. After a chest surgery though, there is often not enough tissue left to physically put where the x-ray beams would actually be able to go through it and create a picture.

Gaby: And here is Dr. Deutsch with an added wrinkle.

Deutsch: I don't have a lot of confidence that a post chest surgery, transmasc person is gonna have a lot of success getting a mammogram done. And so I’d hate to send them for what may already be a dysphoria-inducing study and then have them show up and have like kind of stumbling around and can't get it done.

Sam: And if the test does get done, there's concern for a false positive – meaning a positive test result, but there's no cancer.

Deutsch: We've got studies for cis women have like 50,000 participants looking at test performance to kind of calibrate these tests. We just don't really know with these, with these tests for transmasc people. So the problem is, is that you’re probably gonna wind up having a lot of false positives.

Richard: And when it comes to post mastectomy mammograms, well, we just don't have enough data to know what to chase and what not to, I'm sorry. I know I'm a broken record, but also it's true.

Gaby: And that data is important. Because bodies change all of the time. And some of these changes will look like cancer to the mammogram, and a smaller proportion of those changes will actually be cancerous. Our job is to figure out which cancerous changes are significant enough that we should continue to follow them and actually think about intervening on them.

Deutsch: False positive breast cancer screen is no picnic. It can involve downstream biopsies and you really medicalization of your life.

Sam: For this particular group – meaning those who are post gender affirming mastectomy – it's very hard to know exactly what the benefits of screening with radiology are relative to the potential harms of a false breast cancer scare.

Gaby: But that leads me to my next question - must be Passover because I'm full of questions [laughter] how do we screen for folks who've had these mastectomies? Is there a way that we can assess for chest cancer?

Sam: There are MRIs, but they're not perfect either, which is a bubble. I have to burst a lot when I'm talking to patients.But after someone's had surgeries, there could be a lot of changes in healing that can look like something growing and may not be.

Deutsch: The accuracy of testing when you have somebody whose chest has been surgically altered is not great. We don't have a lot of data on whether it is great or not, but there's no test that's been specifically designed for that.

Gaby: So you're gonna see surgical changes, there’s gonna be less tissue, and the test wasn't designed for this kind of anatomy.

Richard: All of which is going to impact the performance of those. Which, you're trying to use to figure out if you have cancer or not. And that's not something we wanna mess around with.

Sam: Not to mention, insurance frequently does not cover MRIs, which are very expensive out of pocket,

Richard: So again, we're back to not enough data. Even if someone who's had gender affirming surgery can get a screening MRI, we're not really sure what to do with the test results or what they would even mean.

Gaby: Ultimately, Dr. Deutsch does think that a mastectomy lowers your risk of cancer. Even if there's residual tissue there, and even if we don't have any studies examining this lowered risk

Deutsch: And so it becomes kind of – you, you basically wind up having a situation where 90% of your breast tissue has been removed from having your chest operated on. So just on any given day, the likelihood of you having breast cancer is much less because you just have less breast tissue to develop cancer in.

Sam: Dr. Deutsch discusses both of these things in conversations with her patients: both the low likelihood of cancer risk and the low yield of the screening tests.

Deutsch: When you have somebody who likely is not going to have breast cancer, just because they don't have a lot of breast tissue, and then you’re sending them for test that doesn't perform very well…to me, I like to have discussions with the patient and be like, "I'm totally happy to order the test, but I want you to really understand the risks.” And sometimes as a doctor, I worry that patients are like, “Yeah, yeah, doc, whatever, just put in the order.” And I worry about those patients because those are the ones who maybe the next six months, their life is going to be turmoil. because, and then they're going to find them being diagnosed that it was just benign and that's the end of it.

Richard: Definitely don't forgo screening, but remember this when you're considering when to get screened and what that screening might mean to you or may not mean. I think it's totally appropriate to ask your healthcare provider what you're screening for and what you're gonna do with those results if they don't bring it up first.

[TRANSITION MUSIC]

Sam: Let's not gloss over something important that Dr. Deutsch mentioned: being medicalized in the healthcare system is not fun, especially for trans folks who often get medicalized and pathologized at the same time.

Eli: The name and pronoun stuff. When you're going to the doctor once a year, you can shrug it off. But when it's like once a week, it becomes really, really hellacious.

Sam: Beyond just being trans in the healthcare system, Eli also had to deal with the rarity of his diagnosis as a transmasculine person.

Eli: For most of my doctors, I was the first person that they had ever had to had to treat who had all of these factors at the same time. And so there was a degree to which my being sort of a guinea pig was inevitable. But most of the really bad experiences I had were sort of one-offs. The first biopsy I got, the nurse who was doing it wouldn't close the door to the waiting room because, she didn't want to be alone with me in the room. and so I was like sitting there with my shirt off and the door was open. When she like put the needle in, I flinched. She was like, well, if she want to be a man, you're going to have to be tougher.

Richard: And then there's chest cancer as a cultural entity: the pink ribbons, the gendering of breast tissue, the feminine forward aspect of it all.

Eli: It's such an aggressively gendered space. And I think that for so many cis women, having to lose their breasts feels – in addition to just it being traumatic to have cancer for anyone – it feels like such a part of their femininity that the need to sort of reassert femininity in an incredibly aggressive way is like, feels like built sort of baked into some of the cultural content to like be as feminine as possible because this part of your femininity is being taken away from you.

Richard: Even hair loss becomes something that was gendered and in Eli's experience was presented in a way that minimized the impact of losing his hair during chemotherapy.

Eli: Even, like, when I lost my hair, I was, you know, and I was asking questions about it. They were like, "Oh, well, you're, you know, you're a man men don't care about that." You know, like, "Only women care about losing their hair.” Which, you know, there's a multi-billion dollar hair-loss industry that says otherwise about, about cis men too. So I think that was definitely one of the harder things about my experience, both in terms of providers, but also in terms of how I was being looked at by other patients. In terms of, there not really being any support space that I felt comfortable being a part of. I would never have dreamed of going to a support group full of cis women and feeling like I belonged there. So, so it also meant that I just really didn't get the support that is there.

Gaby: Eli ended up finding that support in the form of their chosen family who showed up for them time and time again, physically in person as advocates to the healthcare team.

Eli: Whether it's just to be there with you and be quiet, or whether it's to be loud and obnoxious and advocate for you because you don't feel like you can do it for yourself. Whatever it is that you need. I think having someone with you makes a huge difference. Having someone who wasn't so emotionally distressed be able to like see there and have clear eyes on the situation who really knows me was really a godsend for me. And I'm really lucky to have had chosen family that I really, really, really trust and took care of me.

[TRANSITION MUSIC]

Sam: I hope that transition music changed you as much as it changed me. Just kidding. It's a post edit thing. Anyway, here's the recap. You've been waiting for.

Gaby: Can we just say not enough data and be done with this whole thing?

Sam: Well, tempting Gaby, but no.

Gaby: Okay, let's just start then. First up, testosterone.

Richard: There is a theoretical risk that testosterone may increase the risk of breast cancer by driving the growth of cancerous cells, but this is all based on hypothetical biological models and has never been born out in real world studies. But there are really, really few of those. There's definitely more room for research and clarity here, but do know that the data is clear on testosterone as a life-saving medication for gender affirmation. And so both of these perspectives should be discussed with any trans-masculine person on testosterone who has a breast cancer diagnosis so that they can make an informed decision about how to proceed with their testosterone.

Gaby: We also talked about how anyone considering top surgery would likely benefit from reviewing their own personal and family history for chest cancer. since not all surgeries are equal. Some, particularly those geared towards gender affirmation, leave tissue behind tissue that has the potential to become cancerous.

Richard: If, you've had gender affirming top surgery that leaves you with some of your natal chest tissue, you could still be at risk for breast cancer and might need different types of screenings, and you'll definitely have to discuss that with your healthcare provider.

Gaby: Mammograms, which are our usual go-to screening, depend on there being enough chest tissue for there to be an accurate image. This is almost certainly not going to be the case after a mastectomy. The alternative to a mammogram, a yearly MRI, is unlikely to be covered by insurance.

Sam: And even if you have the imaging, there's so much information that we don't have about what it means and what it doesn't mean that there's a risk of a false positive when interpreting the imaging results.

Richard: The important thing is just to know this when considering any chest altering procedure. We also know that less chest tissue means less risk and more screening doesn't always mean more patients helped. So…

Gaby: I'll take this one, Sam. Not enough data.

Sam: Beautifully said, Gaby. Okay, so that's it from us, but here's Eli with the last word.

Eli: For a lot of young people, you know, you're not thinking about yourself when you're 70. Or, you know, you're not thinking about your risk of cancer and post-menopause when you're 20, you know? And that's just a young person thing that we don't think about that stuff until it becomes real. Even if you're young and you're totally healthy and you don't have any, you know, risk of breast cancer in your family, just to at least have it on your radar. I think this is important.

[QHP THEME MUSIC STARTS]

Gaby: QHP is a power sharing project that puts community stories in conversation with healthcare expertise to expand autonomy for sexual and gender minority folks.

Sam: Thank you to our community voice, Eli Oberman, and our healthcare experts, Dr. Hazen and Dr. Deutsch. We would also like to thank our community reviewer, Preston Allen.

Richard: For more information on this episode's topic, check out our website, www.queerhealthpod.com.

Gaby: Help others find this information by leaving a review and subscribing on Spotify or Apple.

Sam: On Twitter and Instagram, you can find us – meaning Gaby will respond to you - at @QueerHealthPod. So reach out to us. I mean her. I mean us.

Richard: And as always, thank you to Lonnie Ginsburg who composed our theme music.

[QHP THEME MUSIC ENDS]

Gaby: Opinions in this podcast are our own and do not represent the opinions of any of our affiliated institutions. And even though we are doctors, don't use this. podcast alone as medical advice. Instead, consult with your own healthcare provider. BYE.